Note: This post is in regards to an article I published in The Atlantic on October 22 about dismissed Peking University Professor Xia Yeliang. After receiving excessive scorn, I wrote this post a few days later, but ultimately decided it was too long-winded and canned it after I was invited on Sinica to discuss the issue. However, even more than a month later, people continue to misrepresent what I actually wrote and said. Given the gravity of the case, I decided to go ahead and publish it (with a few tweaks). Apologies for the long-windedness…

One thing I’ve learned over the years I’ve been writing about China is that people love simple narratives. In fact, they often demand them. Things are black vs. white, good vs. evil or a brave freedom-fighting David taking on a wholly-despicable Goliath. So if you introduce a little gray, the white camp sees you as representing everything they hate about the black, and vice-versa.

Several years ago at the university I taught at in Nanjing, there was an English professor (a Chinese woman) who would constantly use her classes to aggressively proselytize Christianity to the point that she’d sometimes stand at the podium and tell students they were hell-bound if they didn’t embrace Jesus. Over the years, there were floods of student complaints about her. The school warned her repeatedly, whereupon she’d cool down for a bit, and then quickly return to her old habits. Eventually, she was fired.

But why? This teacher had some fans (many of whom were Christian themselves). There was another, better-connected teacher in the department who did more-or-less the same thing, but she kept her job; whereas the teacher who was fired wasn’t well-liked by her colleagues. And if she’d just as aggressively preached atheism in class, I find it highly unlikely she would have been dismissed in the end. So what did her in? Was it the student complaints, her Christian faith, national politics, office politics, or more likely, some combination of all these things?

I can’t say for sure, but I think it would be a gross over-simplification to yell “religious persecution!” and call it a day. However, that’s exactly what some people on campus did.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve seen a similar thing play out with the case of Xia Yeliang – the Peking University (PKU) economics professor and political dissident who was recently dismissed from his post.

Most people (myself included) initially assumed this was a clear case of political persecution. Given all the very real political persecution happening throughout this country, it wasn’t an unreasonable assumption. A few weeks before the dismissal, I had even asked the head of a Sino-foreign joint venture college in Shanghai how foreign schools could justify “making a deal with the devil” when there are cases like Xia’s.

But then a few days before Xia was officially terminated, I was chatting with a friend studying at PKU. When I mentioned Xia, she said, “Actually, a lot of students at the school are upset with the way the media’s been covering that story.” She said that he was exceptionally unpopular because of his terrible teaching.

Intrigued, I thought I’d follow up on the story and see if it led anywhere. I figured I’d find some fans and some critics, and then pit them against each other in an article. Unfortunately, that’s not what I found.

When I was seeking out students of Xia’s, there were a few types of people I wanted to avoid. Obviously, I didn’t want anyone arranged through Xia himself or PKU. I also didn’t want to cherry-pick commenters on Weibo who, for whatever reason, had self-selected themselves to speak out on the issue. I tend to avoid Weibo and online forums like the plague when reporting – too many people with disingenuous motives. For the same reason, I sure as hell wasn’t going to quote anything or anyone dredged up online where I couldn’t verify that the person was actually a PKU student who had taken Xia’s class. I also didn’t really want to spend time trying to find current students. Xia had known since the beginning of summer that his job was in danger and his dismissal vote was coming up. If it were me, I’d dramatically alter my teaching methods this semester.

I wanted to choose random people who hadn’t yet expressed an opinion and contact them out of the blue. So starting with some contacts I had from PKU (none of whom were employees, Communist Youth League members or anyone with a vested interest or political axe to grind) I started making some calls and sending out queries to try and track down Xia’s students. The secondhand sources I muddled through were relating similar accounts that Xia was widely disliked. Eventually, I landed on four students who had actually taken his classes across several years.

I contacted them out of the blue and separately from one another. Had they started listing the exact same bullet points and buzzwords, I would have been suspicious. However, that wasn’t the case. They all had their own complaints, but there were some consistent themes: that Xia was boastful, dogmatic and preachy in his political beliefs (which he argued incoherently), that he was awful at teaching the subject matter, and that he would spend huge tracts of class time on completely irrelevant topics.

As I was wrapping up the story, PKU came out with a statement (here’s a later English translation) which more-or-less seemed in line with what the students had already told me (in terms of the specific complaints; nobody’s quite sure what’s up with the procedures used to oust Xia).

Had I found a single student that said a positive (or even neutral) word, I would have quoted them in a heartbeat. Unfortunately, I didn’t find this, and I wasn’t about to “balance” out the students I’d methodically sought out in order to avoid bias by quoting an unverifiable and easily manipulated source found through far less methodical means.

I don’t doubt Xia has fans out there though. I can’t think of anyone in history who’s had a 100 percent disapproval rating. But since I didn’t find any of them, I decided I would still present the segment of the student population that felt their voices were being ignored (a segment that seemed pretty large) and then give plenty of room for Xia to respond (but it seems a lot of people missed the half of the article where I laid out Xia’s side of the story).

In the end, I was only able to convince one of the students to use her (English) name in the article. This is something I wrestled with. No journalist likes to use anonymous sources – especially in a situation where they’re criticizing someone else. But having interviewed scores of Chinese students before, I knew that – even on completely benign stories – insistence on anonymity isn’t unusual. Whereas in the West, people are instinctively excited by the prospect of seeing their name in the paper, in China it’s often the opposite – especially among educated people who are well-aware of the country they’re living in (Helen Gao recently did a great piece exploring this). I considered myself lucky that the students even proceeded to talk to me when I said I was a reporter.

This case was extremely politically charged, but the students were more worried about being indicted by the greater public outside of PKU, which was firmly in Xia’s favor. They worried about being labeled wumaodang “50-centers” or CCP-stooges (labels I’ve unsurprisingly been given several times since). So I weighed the gravity of the case, the students’ reasons for wanting anonymity, Xia’s stature as a public figure and the fact that numerous people independently told me similar things. After weighing these things, I decided the story was much better off being told than shelved.

Some have dismissed what I found, saying it was “just a handful of students” and can’t be representative. I agree that it’s not at all on par with a comprehensive scientific survey, but I don’t think it’s negligible either. When two people corroborate the same things, maybe it’s a coincidence; three, a big coincidence. But when you have four people contacted randomly and separately without forewarning corroborating the same things, then that’s enough to make me comfortable that they represent a fairly sizeable group.

This is not the type of article a journalist gets excited about publishing. David vs. Goliath stories are straight-forward and a slam dunk in terms of public reactions. When you report that David might be flawed, however, many people don’t take very kindly to it. I knew I’d get backlash, and that publishing this story would bring me nothing but headaches. But when you find a story like this, you do a great disservice by sitting on it. I knew it would be a lonely few days, but I was more than confident in my reporting. I expected that eventually others would come out and confirm the same things I did, which is indeed what ended up happening (and here and here).

Still, even weeks later, the backlash continues to trickle in – some fair, some absolutely absurd.

The most frequent criticism I’ve gotten goes along the lines of “How can you rule out politics with all the other political repression going on in the country and all the other terrible teachers who are never fired?!” As it turns out, I never did rule out politics. But again, people like latching on to black and white views.

The debate after my article was framed as “Xia Yeliang: bad teacher or victim of politics?” Of course, that’s a false contradiction. There are plenty of possible scenarios involving varying degrees of both of those things. There are indeed countless terrible teachers that are never fired in China, but there are also outspoken dissidents that aren’t fired. Nobody knows for sure why Xia was dismissed though except for his superiors. You can’t rule out politics as a factor or definitively say it was the only factor.

You also shouldn’t ignore aspects of this case just because they complicate the nice neat David vs. Goliath narrative. Academic freedom is an important cause– one that I’ve written on many times – but letting an incomplete narrative prevail doesn’t help that cause; quite the opposite in fact.

Another criticism that I’ve received goes along the lines of “Yes, students are saying these things, but this is China. They’re either brainwashed or being instructed on what to say.” Another variation of this criticism involves the fact that I used to write for Global Times (a newspaper I quit writing for in disgust over two years ago and have written critically of many times since).

According to a group of surprisingly influential professors in the U.S., this is all some conspiracy wherein students were instructed on what to say and, being the government stooge that I am, I gleefully went along with the ruse (never mind that the majority of what I’ve written in the past is critical of the Chinese government – in Global Times, this blog, several Western media outlets and the newspaper I worked at for 18 months that’s nearly been shut down by the government several times).

If it’s easier for you to believe in a massive conspiracy than it is to believe in the possibility that there are real complaints about Xia’s teaching, then fine. I learned long ago not to waste time trying to sway conspiracy theorists.

Were the students told what to say though? Given the way I contacted them (and the other reports that have come out since mine) that would have to involve the university sending out unique instructions to thousands of different students going back seven years – many of whom aren’t even at the school anymore – without the instructions being leaked. If you think that’s a possibility, I suggest you read what happened when this obscure Chinese high school tried that route.

Are the students just brainwashed nationalists taught to hate people like Xia? I suppose I can’t definitively rule that out except to say I bore this possibility in mind while interviewing, and the students I spoke to certainly came off as very open-minded and intelligent.

The students all told me they’re happy (or at least tolerant) to see liberal politics discussed in the classroom in general. Two of them said they were huge fans of He Weifang, a PKU law professor and signatory to Charter 08 who’s been aggressively critical of the government in the classroom.

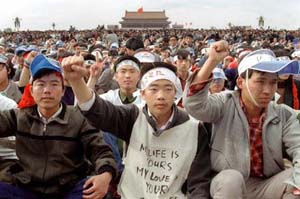

I appreciate all the people who emailed to inform me that China is under a Communist dictatorship (who knew?), to tell me what Chinese universities are REALLY like, and to explain that I was duped into writing this piece. But to anyone who’s spent even a cursory amount of time in a Chinese university over the past few years, the idea that Chinese college students are all programmed conformist robots that would unanimously fall in line when pushed to do so should be patently absurd.

While plenty do ride the herd mentality, there are A LOT of independent individualists out there today that wouldn’t think twice about speaking out against injustice if they saw it. Again, see what happened at this much lesser school when administrators pushed students to fall in line. And let’s not forget about the college students across the country that uploaded pictures of themselves with their faces shown to support Southern Weekend in the name of free speech and democracy last January.

Also, if you’re going to believe the “brainwashed” angle, you have to believe that Valentina Luo, a former researcher for The Telegraph and AFP, is also brainwashed (or in on the massive conspiracy with me).

Some have said since Xia has been branded a political pariah, students who support him wouldn’t dare speak out now; so it’s useless to try and get balanced comment on his teaching from student interviews. This seems like a big cop out to me – one that conveniently allows people to dismiss information that challenges their views. Why not try to randomly contact multiple students out of the blue and see what they say? I know that in the internet era, which allows people to simply quote from Weibo and “report” in their pajamas, actually speaking to people has become a novel concept. But catching them off guard is the best way to get their true feelings. So if they really loved Xia, perhaps they’d say so. See if they’ll even say something supportive anonymously. Heck, even if they hang up the phone, that would tell you something.

Tracking these people down takes effort though – a lot more effort than it takes to track down Xia Yeliang. But if people wanted to challenge what I and other reporters have found, this seems like the best way to do so.

Still, the debate goes on…which it should. There are many unanswered questions. There are ideological politics, office politics, and at Chinese state-run institutions, often a very blurry line between the two. I don’t doubt for one second that there are political components to Xia’s story. As I addressed in my article, Xia sees some big irregularities in the university’s position and the dismissal procedures, which need to be clarified.

Skepticism is good. I absolutely welcome RATIONAL skepticism of my piece and my work in general. But in the absence of any concrete evidence, skepticism should be divvied out to all sides. People who are skeptical of my piece should ask themselves honestly if they applied that same skepticism to earlier reports that sourced nobody other than Xia himself.

People (especially those not actually in China) should also remember that even though the country has scarcely changed politically in the past few years, it’s changed by leaps and bounds socially.Things can get more complicated than we’re able to fully comprehend. This government does indeed give us plenty of clear cut black and white, good vs. evil stories. So it makes it all the easier to miss the complications when things aren’t so simple. The story I did is certainly a complication I would have missed had it not been for a random conversation I had with a PKU student.

That conversation allowed me to realize that my initial knee-jerk bias meant I wasn’t as critical of the prevailing narrative as I should have been. When a fair number of people who had firsthand experience with Xia challenged my assumptions, I REPORTED what they said (which is quite different than ENDORSING what they said). You can make your own judgments about why they said it or if it warrants a dismissal. I expected to get quite a bit of heat for this piece, but at the end of the day, self-respecting reporters can’t sit on stories just because they don’t like their implications. I believe I did this story fairly and as thoroughly as the circumstances allowed, so I stand by it without regrets.

employers to assist in medical fees; either through insurance or out of their

employers to assist in medical fees; either through insurance or out of their